Tesla gives us a history lesson along with some of Zmai's poetry in this article from The Century Illustrated Magazine. Robert Underwood Johnson and Nikola Tesla worked on the poem translations together.

The Century Illustrated Magazine, January 1, 1894, Scribner & Company, Pages 130-133.

ZMAI IOVAN IOVANOVICH.

THE CHIEF SERVIAN POET.

HARDLY is there a nation which has met with a sadder fate than the Servian. From the height of its splendor, when the empire embraced almost the entire northern part of the Balkan peninsula and a large portion of the territory now belonging to Austria, the Servian nation was plunged into abject slavery, after the fatal battle of 1389 at the Kosovo Polje, against the overwhelming Asiatic hordes. Europe can never repay the great debt it owes to the Servians for checking, by the sacrifice of their own liberty, the barbarian influx. The Poles at Vienna, under Sobieski, finished what the Servians attempted, and were similarly rewarded for their service to civilization.

HARDLY is there a nation which has met with a sadder fate than the Servian. From the height of its splendor, when the empire embraced almost the entire northern part of the Balkan peninsula and a large portion of the territory now belonging to Austria, the Servian nation was plunged into abject slavery, after the fatal battle of 1389 at the Kosovo Polje, against the overwhelming Asiatic hordes. Europe can never repay the great debt it owes to the Servians for checking, by the sacrifice of their own liberty, the barbarian influx. The Poles at Vienna, under Sobieski, finished what the Servians attempted, and were similarly rewarded for their service to civilization.It was at the Kosovo Polje that Milosh Obilich, the noblest of Servian heroes, fell, after killing the sultan Murat II, in the very midst of his great army. Were it not that it is a historical fact, one would be apt to consider this episode a myth, evolved by contact with the Latin and Greek races. For in Milosh we see both Mucius and Leonidas, and, more than this, a martyr, for he does not die an easy death on the battle-field like the Greek, but pays for his daring deed with a death of fearful torture. It is not astonishing that the poetry of a nation capable of producing such heroes should be pervaded with a spirit of nobility and chivalry. Even the indomitable Marko Kraljevich, the later incarnation of Servian heroism, when vanquishing Musa, the Moslem chief, exclaims, "Woe unto me, for I have killed a better man than myself!"

From that fatal battle until a recent period, it has been black night for the Servians, with but a single star in the firmament -- Montenegro. In this gloom there was no hope for science, commerce, art, or industry. What could they do, this brave people, save to keep up the weary fight against the oppressor? And this they did unceasingly, though the odds were twenty to one. Yet fighting merely satisfied their wilder instincts. There was one more thing they could do, and did: the noble feats of their ancestors, the brave deeds of those who fell in the struggle for liberty, they embodied in immortal song. Thus circumstances and innate qualities made the Servians a nation of thinkers and poets, and thus, gradually, were evolved their magnificent national poems, which were first collected by

From that fatal battle until a recent period, it has been black night for the Servians, with but a single star in the firmament -- Montenegro. In this gloom there was no hope for science, commerce, art, or industry. What could they do, this brave people, save to keep up the weary fight against the oppressor? And this they did unceasingly, though the odds were twenty to one. Yet fighting merely satisfied their wilder instincts. There was one more thing they could do, and did: the noble feats of their ancestors, the brave deeds of those who fell in the struggle for liberty, they embodied in immortal song. Thus circumstances and innate qualities made the Servians a nation of thinkers and poets, and thus, gradually, were evolved their magnificent national poems, which were first collected by

their most prolific writer, Vuk Stefanovich Karajich, who also compiled the first dictionary of the Servian tongue, containing more than 60,000 words. These national poems Goethe considered fit to match the finest productions of the Greeks and Romans. What would he have thought of them had he been a Servian?

their most prolific writer, Vuk Stefanovich Karajich, who also compiled the first dictionary of the Servian tongue, containing more than 60,000 words. These national poems Goethe considered fit to match the finest productions of the Greeks and Romans. What would he have thought of them had he been a Servian?While the Servians have been distinguished in national poetry, they have also had many individual poets who attained greatness. Of contemporaries, there is none who has grown so dear to the younger generation as Smai Iovan Iovanovich. He was born in Novi Sad (Neusatz), a city at the southern border of Hungary, on November 24, 1833. He comes from an old and noble family, which is related to the Servian royal house. In his earliest childhood he showed a great desire to learn by heart the Servian national songs which were recited to him, and even as a child he began to compose poems. His father, who was a highly cultivated and wealthy gentleman, gave him his first education in his native city. After this he went to Budapest, Prague, and Vienna, and in these cities he finished his studies in law. This was the wish of his father, but his own inclinations prompted him to take up the study of medicine. He then returned to his native city, where a prominent official position was offered him, which he accepted, but so strong were his poetical instincts that a year later he abandoned the post to devote himself entirely to literary work.

His literary career begain in 1849, his first poem being printed in 1852, in a journal called "Srbski Letopis" ("Servian Annual Review"); to this, and to other journals, notably "Neven" and "Sedmica," he contributed his early productions. From that period until 1870, besides his original poems, he made many beautiful translations from Petefy and Arany, the two greatest of the Hungarian poets, and from the Russian of Lermontof, as well as from German and other poets. In 1861 he edited the comic journal, "Komarac" ("The Mosquito"), and in the same year he started the literary journal, "Javor," and to these papers he contributed many beautiful poems. He had married in 1861, and during the few happy years that followed he produced his admirable series of lyrical poems called "Giulichi," which probably remain his masterpiece. In 1862, greatly to his regret, he discontinued his beloved journal,

His literary career begain in 1849, his first poem being printed in 1852, in a journal called "Srbski Letopis" ("Servian Annual Review"); to this, and to other journals, notably "Neven" and "Sedmica," he contributed his early productions. From that period until 1870, besides his original poems, he made many beautiful translations from Petefy and Arany, the two greatest of the Hungarian poets, and from the Russian of Lermontof, as well as from German and other poets. In 1861 he edited the comic journal, "Komarac" ("The Mosquito"), and in the same year he started the literary journal, "Javor," and to these papers he contributed many beautiful poems. He had married in 1861, and during the few happy years that followed he produced his admirable series of lyrical poems called "Giulichi," which probably remain his masterpiece. In 1862, greatly to his regret, he discontinued his beloved journal,

"Javor"--a sacrifice which was asked of him by the great Servian patriot, Miletich, who was then active on a political journal, in order to insure the success of the latter.

"Javor"--a sacrifice which was asked of him by the great Servian patriot, Miletich, who was then active on a political journal, in order to insure the success of the latter.In 1863 he was elected director of an educational institution, called the Tekelianum, at Budapest. He now ardently renewed the study of medicine at the university, and took the degree of doctor of medicine. Meanwhile he did not relax his literary labors. Yet for his countrymen, more valuable even than his splendid productions were his noble and unselfish efforts to nourish the enthusiasm of Servian youth. During his stay in Budapest he founded the literary society Preodnica, of which he was president, and to which he devoted a large portion of his energies.

In 1864 he started his famous satirical journal, "Zmai" ("The Dragon"), which was so popular that the name became a part of his own. In 1866 his comic play "Sharan" was given with great success. In 1872 he had the great pain of losing his wife and, shortly after, his only child. How much these misfortunes affected him is plainly perceptible from the deeply sad tone of the poems which immediately followed. In 1873 he started another comic journal, the "Ziza." During the year 1877 he began an illustrated chronicle of the Russo-Turkish was, and in 1878 appeared his popular comic journal, "Starmali." During all

this period, he wrote not only poems, but much prose, including short novels, often under an assumed name. The best of these is probably "Vidosava Brankovicheva." In recent years he has published a great many charming little poems for children.

this period, he wrote not only poems, but much prose, including short novels, often under an assumed name. The best of these is probably "Vidosava Brankovicheva." In recent years he has published a great many charming little poems for children.Since 1870 Zmai has pursued his profession as a physician. He is an earnest advocate of cremation, and has devoted much time to the furtherance of that cause. Until recently he was a resident of Vienna, but now he is domiciled in Belgrade. There he lives the life of a true poet, loving all and beloved by everybody. In recognition of his merit, the nation has voted him a subvention.

The poems of Zmai are so essentially Servian that to translate them into another tongue appears next to impossible. In keen satire free from Voltairian venom, in good-hearted and spontaneous humor, in delicacy and depth of expression, they are remarkable. Mr. Johnson has undertaken the task of versifying a few of the shorter ones after my literal and inadequate readings. Close translation being often out of the question, he has had to paraphrase, following as nearly as possible the original motives and ideas. In some instances he has expanded in order to complete a picture or to add a touch of his own. The four poems which follow will give some idea of the versatility of the Servian poet, but come far short of indicating his range.

Nikola Tesla.

PARAPHRASES FROM THE SERVIAN.

AFTER ZMAI IOVAN IOVANOVICH.

THE THREE GIAOURS.

IN the midst of the dark and stormy night

Feruz Pacha awakes in fright,

And springs from out his curtained bed.

The candle trembles as though it read

Upon his pallid face the theme

And terror of his nightly dream.

He calls to his startled favorite:

"The keys! the keys of the dungeon-pit!

Cannot those cursed Giaours stay

There in their own dark, rotting away,

Where I gave them leave three years ago?

Had I but buried their bones!—but, no!

They come at midnight to clatter and creep,

And haunt and threaten me in my sleep."

"Pacha, wait till the morning light!

Do not go down that fearful flight

Where every step is a dead man's moan!

Mujo to-morrow will gather each bone

And bury it deep. Let the Giaours freeze

If thy bed be warm."

"Nay, give me the keys.

Girl, you talk like a wrinkled dame

That shudders at whisper of a name.

When they were living, their curses made

A thousand cowards: was I afraid?

Now they are dead, shall my fear begin

With the Giaour's curse, or the skeleton's grin?

No, I must see them face to face

In the very midst of their dwelling-place,

And find what need they have of me

That they call my name eternally."

As groping along to the stair he goes

The light of the shaking candle shows

A face like a white and faded rose;

But if this be fear, it is fear to stay,

For something urges him on his way—

Though the steps are cold and the echoes mock—

Till the right key screams in the rusted lock.

Ugh! what a blast from the dungeon dank!—

From the place where Hunger and Death were wed;

Whence even the snakes by instinct fled,

While the very lizards crouched and shrank

In a chill of terror. 'T is inky black

And icy cold, but he cannot go back,

For there, as though the darkness flowers—

There sit the skeletons of three Giaours

Ghost-white in the flickering candle-gleam!—

(Or is it the remnant of his dream?)

About a stone that is green with mold

They sit in a group, and their fingers hold

Full glasses, and as the glasses clink

The first Giaour beckons him to drink.

"Pacha, here is a glass for thee!

When last on me the sunlight shone

I had a wife who was dear to me.

She was alone—no, not alone;

The blade in her hand was her comrade true,

As she came to your castle, seeking you.

"And when she came to your castle gate

She dared you forth, but you would not go.

Fiend and coward, you could not wait

For a woman's wrath, but shot her, so.

Her heart fell down in a piteous flood.

This glass is filled with her precious blood.

"See how fine as I hold it up!

Drink, Feruz Pacha, the brimming cup!"

Spellbound the Pacha now draws nigh;

He empties the glass with a sudden cry:

The skeletons drink with a laugh and toss,

And they make the sign of the holy cross.

Then speaks the second of the dead:

"When to this darkness I was led,

My mother asked, 'What sum will give

Your prisoner back to the sun?' You said,

'Three measures of gold, and the dog shall live.'

Through pinching toil by noon and night

She saved and saved till her hope grew bright.

"But when she brought you the yellow hoard,

You mocked at the drops on her tired brow,

And said, 'Toward the pay for his wholesome board

Of good round stones I will this allow.'

She died while her face with toil was wet.

This glass is filled with her faithful sweat.

"See how fine as I hold it up!

Drink, Feruz Pacha, the brimming cup!"

Haggard the Pacha now stands by;

He drains the glass with a stifled cry:

Again they drink with a laugh and toss,

And the third one says, as his comrades cross:

"When this black shadow on me fell,

There sang within my mountain home

My one pale lad. Bethought him well

That he would to my rescue come;

But when he tried to lift the gun

He tottered till the tears would run.

"Though vengeance sped his weary feet,

Too late he came. Then back he crept,—

Forgot to drink, forgot to eat,—

And no slow moment went unwept.

He died of grief at his meager years.

This glass is laden with his tears.

"See how fine as I hold it up!

Drink, Feruz Pacha, the brimming cup!"

The Pacha staggers; he holds it high;

He drinks; he falls with a moan and cry:

They laugh, they cross, but they drink no more—

For the dead in the dungeon-cave are four.

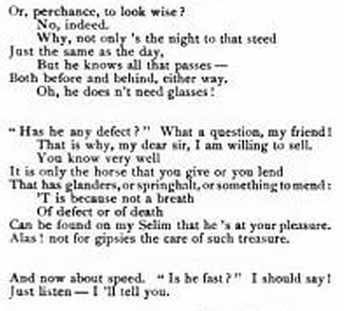

THE GIPSY PRAISES HIS HORSE.

You're admiring my horse, sir, I see.

He's so light that you'd think it's a bird,

Say a swallow. Ah me!

He's a prize!

It's absurd

To suppose you can take him all in as he passes

With the best pair of eyes,

Or the powerful aid

Of your best pair of glasses:

Take 'em off, and let's trade.

What! “Is Selim as good as he seems?”

Never fear,

Uncle dear,

He's as good as the best of your dreams,

And as sound as your sleep.

It's only that kind that a gipsy would keep.

The emperor's stables can't furnish his mate.

But his grit and his gait,

And his wind and his ways,

A gipsy like me doesn't know how to praise.

But (if truth must be told)

Although you should cover him over with gold

He 'd be worth one more sovereign still.

“Is he old?”

Oh, don't look at his teeth, my dear sir!

I never have seen 'em myself.

Age has nothing to do with an elf;

So it 's fair to infer

My fairy can never grow old.

Oh, don't look—(Here, my friend,

Will you do me the kindness to hold

For a moment these reins while I 'tend

To that fly on his shanks?)...

As I said—(Ah—now—thanks!)

The longer you drive

The better he'll thrive.

He'll never be laid on the shelf!

The older that colt is, the younger he'll grow.

I've tried him for years, and I know.

“Eat? Eat?” do you say?

Oh, that nag isn't nice

About eating! Whatever you have will suffice.

He takes everything raw—

Some oats or some hay,

Or a small wisp of straw,

If you have it. If not, never mind—

Selim won't even neigh.

What kind of a feeder is he? That's the kind!

“Is he clever at jumping a fence?”

What a question to ask! He's immense

At a leap!

How absurd!

Why, the trouble's to keep

Such a Pegasus down to the ground.

He takes every fence at a bound

With the grace of a bird;

And so great is his strength,

And so keen is his sense,

He goes over a fence

Not across, but the way of its length!

“Under saddle?” No saddle for Selim!

Why, you've only to mount him, and feel him

Fly level and steady, to see

What disgrace that would be.

No, you couldn't more deeply insult him, unless

You attempted to guess

And pry into his pedigree.

Now why should you speak of his eyes?

Does he seem like a horse that would need

An eye-glass to add to his speed

Or, perchance, to look wise?

No indeed.

Why, not only's the night to that steed

Just the same as the day,

But he knows all that passes—

Both before and behind, either way.

Oh, he doesn't need glasses!

“Has he any defect?” What a question, my friend!

That is why, my dear sir, I am willing to sell.

You know very well

It is only the horse that you give or you lend

That has glanders, or springhalt, or something to mend:

'T is because not a breath

Of defect or of death

Can be found on my Selim that he's at your pleasure.

Alas! not for gipsies the care of such treasure.

And now about speed. “Is he fast?” I should say!

Just listen—I'll tell you.

One equinox day,

Coming home from Erdout in the usual way,

A terrible storm overtook us. 'T was plain

There was nothing to do but to run for it. Rain,

Like the blackness of night, gave us chase. But that nag,

Though he'd had a hard day, didn't tremble or sag.

Then the lightning would flash,

And the thunder would crash

With a terrible din.

They were eager to catch him; but he would just neigh,

Squint back to make sure, and then gallop away.

Well, this made the storm the more furious yet,

And we raced and we raced, but he wasn't upset,

And he wouldn't give in!

At last when we got to the foot of the hill

At the end of the trail,

By the stream where our white gipsy castle was set,

And the boys from the camp came a-waving their caps,

At a word he stood still,

To be hugged by the girls and be praised by the chaps.

We had beaten the gale,

And Selim was dry as a bone—well, perhaps,

Just a little bit damp on the tip of his tail.[1]

[1] Readers will be reminded by this conclusion of Mark Twain's story of the fast horse as told to him by Oudinot, of the Sandwich Islands, and recorded in “The Galaxy” for April, 1871. In that veracious narrative it is related that not a single drop fell on the driver, but the dog was swimming behind the wagon all the way.

MYSTERIOUS LOVE.

Into the air I breathed a sigh;

She, afar, another breathed -

Sighs that, like a butterfly,

Each went wandering low and high,

Till the air with sighs was wreathed.

When each other long they sought,

On a star-o'er-twinkled hill

Jasmine, trembling with the thought,

Bothe within her chalice caught,

A lover's potion to distil.

Drank of this a nightingale,

Guided by the starlight wan -

Drank and sang from dale to dale,

Till every streamlet did exhale

Incense to the waking daawn.

Like the dawn, the maiden heard;

While, afar, I felt the fire

In the bosom of the bird;

Forth our sighs again were stirred

With a sevenfold desire.

These we followed till we learned

Where they trysted; there erelong

Their fond nightingale returned.

Deeper then our longings burned,

Deeper the delights of song.

Now, when at the wakening hour,

Sigh to sigh, we greet his lay,

Well we know its mystic power -

Feeling dawn and bird and flower

Pouring meaning into May.

Jasmine, perfume every grove!

Nightingale, forever sing

To the brightening dawn above

Of the mystery of love

In the mystery of spring!

TWO DREAMS.

DEEP on the bosom of Jeel-Begzad

(Darling daughter of stern Bidar)

Sleeps the rose of her lover lad.

It brings this word : When the zenith-star

Melts in the full moon's rising light,

Then shall her Giaour come to-night.

What is the odor that fills her room?

Ah! 't is the dream of the sleeping rose:

To feel his lips near its velvet bloom

In the secret shadow no moonbeam knows,

Till the maiden passion within her breast

Kindles to flame where the kisses rest.

By the stealthy fingers of old Bidar

(Savage father of Jeel-Begzad)

Never bloodless in peace or war

Was a hand jar sheathed; and each one had

Graved on its handle a Koran prayer--

He can feel it now, in his ambush there!

The moon rides pale in the quiet night;

It puts out the stars, but never the gleam

Of the waiting blade's foreboding light,

Astir in its sheath in a horrid dream

Of pain, of blood, and of gasping breath,

Of the thirst of vengeance drenched in death.

* * *

The dawn did the dream of the rose undo,

But the dream of the sleeping blade came true.